British radical and chartist publications archived at the Centre of Social and Political History, Moscow

- Structure of archive

- Pamphlets and books

- Newspapers and periodicals

- Russian State Library serials

- Links to other archives

A short history of the ‘English Cabinet’ (Кабинет Англии)

by Peter Sinclair

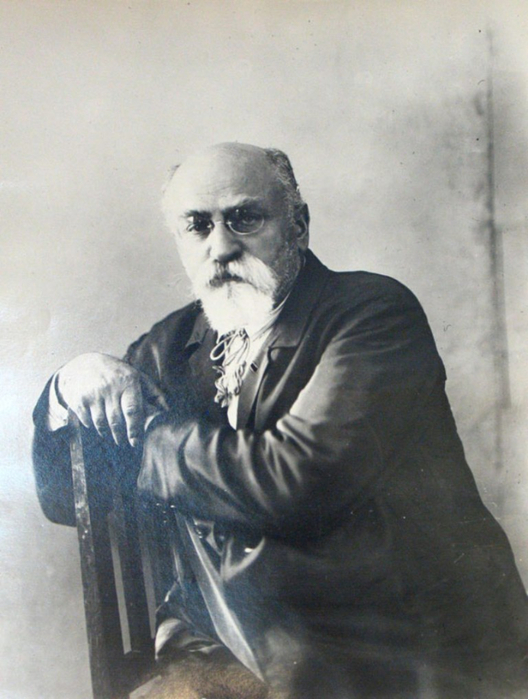

The man behind the creation of the archive that housed the ‘English Cabinet’ was David Riazanov [David Borisovitch Goldendach] (1870–1938).[1] Riazanov, a political activist from the age of seventeen, was arrested and deported twice by the Tsarist regime. After he returned to Russia in 1917 he joined the Bolshevik Party and took part in the October revolution. He created the Archive Centre in 1918 and helped to set up the Socialist Academy of Social Sciences the same year. When the new Marx-Engels Institute was founded as a branch of the Academy the following year, Riazanov became its first director. In 1920 the Institute was installed in a building that had been the town residence of the Dolgorukov princes in Moscow’s Znamenka quarter.

According to a pamphlet published in 1929, Riazanov said that the Central Committee of the Communist Party had originally proposed that he organise a ‘Museum of Marxism’. He, however, envisaged something greater, more important, and also more useful. He obtained its permission to create a scientific institute, a sort of ‘laboratory’, where historian and activist alike could study ‘in the most favourable conditions the birth, development and spread of the theory and practice of scientific socialism’, whose aim was to contribute the utmost ‘to the scientific propaganda of Marxism’.[2]

His first acquisitions for the Institute were from the recently nationalised libraries, among them that of Taniéev, which contained an excellent collection of socialist authors and a rare collection of prints from the time of the French revolution. However, socialist publications had never been freely admitted into Russia, so Riazanov looked further afield. He purchased the library of Theodor Mautner, a socialist book-lover, the library of Karl Grünberg, an historian of socialism, and that of M. Windelband, consisting of philosophical works. Endowed with an exceptional memory and capacity for work Riazanov undertook intensive research in the archives and great European libraries, arranging for the purchase of books, pamphlets and newspapers to complete the Institute’s collections, where necessary having manuscripts and documents photographed, whilst at the same time directing the Institute and organising exhibitions.

A contemporary described Riazanov about that time:[3]

The impression he left was one of immense, almost volcanic energy – his powerful build added to this impression – and tireless in collecting every scrap about, or pertaining to, Marx and Engels. His speeches at party congresses, marked by great wit, often carried him in sheer enthusiasm beyond the bounds of logic. He did not hesitate to cross swords with anyone, not even with Lenin. He was treated for this reason with rather an amused respect, as a kind of caged lion, but one whose bark or growl usually had a grain or two of truth worth listening to.

The collections he brought together at the Institute were arranged in different sections or ‘cabinets’ and formed two series. The ideological series included sections on philosophy (25,000 volumes); socialism, where the Mautner, Grünberg and Taniéev collections were deposited; political economy (20,000 volumes); sociology; law and politics, with archives attached to each cabinet. The historical series included cabinets for German-language books, the richest (50,000 volumes), French (almost 40,000 volumes), English and other languages. On 20 May 1922, Riazanov wrote to A. F. Rothstein and A. A. Bogdanov, about the ‘Кабинет Англии’ (English Cabinet):[4]

We appreciate the great role that England played in the history of socialism and the labour movement. We set up a special cabinet for this, in this office, along with general works on the history of England. We collected a rich collection for studying the history of the English people and workers’ movements. We have a beautiful collection of pamphlets, in addition, first editions of Bellers, Winstanley, Harrington. We also have a rich collection of magazines from the first quarter of the 19th century. Our collection of the first editions of Owen is not inferior to the collection in the British Museum. The section on Chartism is second only to the British Museum. In the English Cabinet there worked such well-known experts on English history as D. Petrushevsky and A. Savin.

In 1924, with Riazanov’s approval, the Socialist Academy was renamed the Communist Academy to allow Marxists to research problems independent of, and implicitly in rivalry with, the Academy of Sciences.[5] He wrote, ‘I am not a Bolshevik, I am not a Menshevik, I am not a Leninist. I am only a Marxist, and, as a Marxist, I am a communist.’[6] That year the Marx-Engels Institute was included amongst the cultural establishments of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and as such was recognised as a state institution and functioned – in view of its exceptional importance – under the immediate control of the Central Committee. The Communist Academy was abolished by Stalin in 1936.[7] Of the 109 people employed by the Institute in 1930, 87 were historians and, as indication of its independence, only 39 of its staff members were members of the Communist Party.[8] This did not go unnoticed. In an otherwise favourable resolution of June 1929, the party’s Central Committee observed that the Institute’s activity was ‘weakly linked with the broad scientific and party community’.[9]

By 1931, the Institute’s archives contained 15,000 manuscripts from the heirs of Karl Marx, and some of the rarest publications on which they had collaborated, including Vorwärts published by Marx in Paris in 1844 and the Rheinische Zeitung of 1842–43. They also included records of the German Socialist Party, and personal papers of a wide range of European socialists, including the private collections of Eduard Bernstein, and

…a very fine collection on the French revolution, with the works and publications of Marat, Robespierre, Anacharsis Clootz, and Babeuf in first editions, the very rare brochures and pamphlets of the Enragés, the most precious periodicals, such as the Ami du Peuple, the Père Duchesne, the Tribun du Peuple, etc.; a complete collection, also in the original editions, of the works of Robert Owen , including many brochures, manifestos, etc., not mentioned in the remarkable Bibliography of Robert Owen (2nd enlarged edition, 1925); a remarkable collection of the British economists; an almost complete collection of the periodicals of 1848 (over 400 titles), and most of the publications relating to the events of 1848 in the various countries; and the main publications of the working class and on the working-class movement, etc.

Among recent acquisitions we might mention a file of The Times from its foundation to the war; a very rare file of the New York Tribune, including the years when Marx and Engels collaborated with it; the unique collection of M. Helfert, wholly devoted to the revolutionary movement of 1848–49 in Austria, Hungary, Italy and the Slav countries, amounting to 5000 volumes, 10,000 posters, placards, proclamations, etc., 4500 prints and portraits, and 1000 autograph letters; a collection of manuscripts, most of them unpublished, of Gracchus Babeuf, including his letters to his son Emil, his wife, and his writings during the trial; and a remarkable collection of posters, placards, cartoons and other documents from the time of the Commune.

Among the publications of the Institute was the monumental edition of the works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, and the journals Marx-Engels Archives and the Annals of Marxism, which Riazanov founded and edited, rich in studies and documentary notes written by him. He edited the Marxist Library, including the foremost edition of The Communist Manifesto, which he annotated, the Library of Materialism (Holbach, Hobbes, Diderot, Feuerbach, La Mettrie, J. Toland, Gassendi, Helvetius and Priestley), the Complete Works of G. V. Plekhanov, those of Karl Kautsky and Paul Lafargue, Hegel’s philosophical works, the Library of the Classics of Political Economy, and more.

Riazanov celebrated his sixtieth birthday in March 1930 and was showered with praise by the Soviet press. But in February the following year, as a result of being implicated in the Menshevik Trial by Isaak Rubin, a former employee of the Institute, Riazanov was arrested and accused of hiding Menshevik documents at the Institute. He was dismissed as its director in February 1931, expelled from the Communist Party and subjected to administrative exile in the city of Saratov. The work of the Institute was suspended and almost all his collaborators were recalled. Kirov granted him permission to return to Leningrad, but after Kirov’s assassination in 1934 he had to return to Saratov, where he worked in a university library. He was arrested again in 1937 and accused of being a member of a ‘right-opportunist Trotskyist organisation’. On 21 January 1938, following a perfunctory trial, the Military Collegium of the USSR Supreme Court condemned him to death and he was executed later that day.[10]

Following the purge of the Institute, it was merged with the slightly larger Lenin Institute in November 1932 to form the Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute. The Lenin Institute had been founded by the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party in September 1923 to gather manuscripts for the publication of a scholarly edition of Lenin’s collected works. In 1924 its mission was expanded by the 13th Congress of the Russian Communist Party to include the ‘study and dissemination of Leninism among the broad masses within and outside the party’. In 1952 ‘of the CC CPSU’ was attached to the Institute’s name, and from 1954 it became the Marx-Engels-Lenin-Stalin Institute of the CC CPSU. After Khrushchev’s famous speech in 1956 it was changed to the Institute of Marxism-Leninism of the CC CPSU, or IML, by which it was known during the years when the Marx Memorial Library was developing closer links with it.

The IML moved to a new building in 1960 at 4 Wilhelm Pieck Street. It had previously been occupied by the International Lenin School in the 1930s and for five years by the Comintern (Communist International). It has been the home of the Russian State Social University since 2003. The name of the IML was changed to the Institute of the Theory and History of Socialism of the CC CPSU between April and October 1991. It formally ceased to exist in November 1991 after all CPSU archives were nationalised by presidential decree on 24 August 1991. The Marx-Engels Museum was abolished in 1993 and its archival holdings were transferred to the Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (RGASPI).[11]

The IML English-language library archives are now (2017) held at the Centre of Social and Political History, which is part of the State Public Historical Library.[12] The collection has not been separately catalogued or digitised and can only be accessed by visiting the Centre and requesting a title. The address of the Centre is Wilhelm Pieck str., 4-2, 129226 Moscow. Nearest Metro: Botanicheskiy Sad (Ботанический сад). Its current director is Mrs Elena Nikolajevna Strukova, who can be reached at +7 (499) 187-99-45. The senior bibliographer is Irina Getman, +7 (499) 181-50-37. Other consultants can be reached at +7 (499) 181-44-65 and +7 (499) 181-17-05. The email address of the Centre is reference@shpl.ru.

FOOTNOTES

[1] For much of the detail about Riazanov and the Institute I must acknowledge two articles, one by ‘L. B.’ entitled ‘The Marx-Engels Institute’ and translated from La Critique sociale, 2 (July 1931), 51–52, and the second by Boris Souvarine entitled ‘D. B. Riazanov’ and translated from La Critique sociale, 2 (July 1931), 49–50, at https://www.marxists.org/archive/riazanov/, accessed 10 August 2017. Also ArcheoBiblioBase: Archives in Russia: B-12 at http://ww.iisg.nl/abb/rep/B-12.tab2.php, accessed 13 February 2017.

[2] https://www.marxists.org/archive/riazanov/bio/bio2.htm, accessed 10 August 2017.

[3] https://www.marxists.org/archive/riazanov, accessed 10 August 2017.

[4] RGASPI, p. 71, op. 50, е.х.1, p. 66, cited at http://filial.shpl.ru/kabinet-anglii, accessed 10 August 2017.

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Communist_Academy, accessed 12 September 2017.

[6] Newsletter of the Communist Academy, no. 8, Moscow, 1924, cited at https://www.marxists.org/archive/riazanov/, accessed 10 Aug 2017.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Barber, John (1981). Soviet Historians in Crisis, 1928–1932. London: Macmillan, p. 16, citing Institut K. Marksa i F. Engel’sa pri TsIK SSSR (Moscow, 1930), p. 61.

[9] Ibid., citing ‘Postanovlenie TsK VKP (b) ot 14 iyunya 1929 g.’ in Institut K. Marksa i F. Engel’sa pri TsIK SSSR (Moscow, 1930), pp. 72–75.

[10] Day, Richard and Daniel Gaido, eds. (2011). Witnesses to Permanent Revolution: The Documentary Record [2009]. Chicago: Haymarket Books, p. 70, cited at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Riazanov, accessed 12 September 2017.

[11] http://www.iisg.nl/abb/rep/B-12.tab2.php, accessed 13 February 2017.